The Time I Might’ve Got Croaked

All cotton ain’t candy.

There was ample lore surrounding Caddo Lake in deep East Texas. The dark glades and the mossy tapestries draped from the trees made it humbling, and oddly a bit reverent. Some of the folks there believed that to be “saved,” in the non-spiritual sense, it was necessary to remove the “City” from the “Boy”. There were many acceptable ways to do that, including bloodletting by pond leeches, or wading thigh-deep through Alligator Pass in the dark of the moon. Oh—and there was one other way.

My friend Turk Henry was a river rat of the sixth degree, having been raised by fifth-generation Caddo people, and having actually attended Karnack public schools. Karnack Texas was the celebrated home of Lady Bird Johnson, even before she was anybody but T.J. Taylor’s daughter. T.J. operated a general store in Karnack, with a no-nonsense advertisement above the door that proclaimed him “Dealer in Everything”. Other than T.J.’s store, the only other asterisk on Karnack’s dot on the map belonged to its Army Ammunition Depot, which probably placed the town on every Soviet spy map as well.

Turk’s life was the river, and his sport was to harvest its bullfrogs. Slay Henry, Turk’s dad, kept a number of flat bottom boats resting on the bank under the house. Warped and bent from countless forays against cypress knees, each boat had been given a name, so that Slay could properly identify each member of his little fleet. “In case they get stole,” he said. Of the four boats, “Old Yellaw” was Turk’s favorite, because of its “shaller draft.”

One day the two of us were sitting in Old Yellaw, which was beached beside the house. Turk’s dad stepped out on the porch, and sensing that we might be bored, offered up an idea.

“Turk, take the City Boy gigging. Them Pine Island swamp gasses puts off a certain-teed tonic of purification.” With that, he spat tobacco into the water and mumbled his way back into the house. Except for the “City Boy” label, I was delighted with the suggestion. Being invited to go with Turk on a frog gig was like being asked to the prom by the head twirler.

“Be here at eleven tomorrow night,” Turk said. He too spat into the water as he went inside.

The next night, I showed up at the agreed hour wearing dark clothes and new knee-high rubber boots as instructed. Turk had someone with him, and they were loading things into “Yellaw.”

“First things first.” Turk said. He pointed me to a chair that was glowing yellow from the oil lantern hanging above it. I sat in it, feeling a bit like a courtroom spectator.

“This here is Boze Smitherman,” Turk said, pointing to the stranger. “Boze always gigs with me. He’s the oarsman.” I gave Boze the traditional Southern chin-bob, that head-motion that replaces spoken greetings. He gave me the chin-bob back. It meant that we were now lifelong friends.

Turk began. “Okay, Frog 101. Two things you gotta learn.” As Turk spoke, Boze moved back into the darkness, and resumed his preparations.

Turk continued. “Dead silence is the rule. Frogs have little Doppler radar units on both sides of their head. They are little acoustic membranes shaped like kettledrum covers, and they are so sensitive they can tell if you are even thinking about making noise. Secondly, frogs are equipped with little shooters. They squirt when you grab them, and can shoot their stream at very precise angles—your eye, or worse, your mouth. And guess what? It ain’t river water they’re squirting.”

Having been trained in the two essential lessons for the night, we piled into old Yellaw and pushed off. Our job descriptions were simple. Turk did the gigging from the prow; I did the sacking in the middle seat, and Boze skulled the boat from the rear. As we moved down the channel into Pine Island Slough, both of them warned me one last time about noise. There was to be nothing but whispered conversation beyond this point. As we slid silently through the darkness, I held tightly to the burlap sack, choking its neck as if it already contained a mess of bullfrogs.

We tacked left and right across the slough. Boze seemed to know the perfect route to avoid the random cypress knees. The sounds of midnight became increasingly loud as we navigated through Pine Island, and surrounding us on all sides were the hoarse grrroats of big bullfrogs. Like a choir director, Turk seemed to sense which frog’s sound belonged where.

“Big one over here,” he whispered, gesturing a few degrees to the right. Boze adjusted the direction and we headed straight to the bank. Suddenly, Turk’s flashlight broke the ink of night, and my eyes transfixed on its beam. With a smooth jab, we had our first frog. The handoff went smoothly, and I stuffed the big bullfrog into the sack.

Boze turned the boat to the left, following Turk’s extended arm. “Double-ups,” he whispered. Frog-101 had not explained “double-ups,” but I figured I might need both hands. Turk made two quick thrusts with the gig, and produced two especially large frogs. I was impressed.

The shore was becoming thick with cypress and overhanging bayberry bushes. As we passed underneath vines and brush, Spanish moss flowed over me, trailing across my face and arms like parting cobweb curtains. I began to worry about ticks, because Spanish moss is said to be a favorite breeding ground for deer ticks. Mosquitoes were feasting on my arms and neck, but I did not dare slap at them for fear of making a sound. Just as we passed beneath a large river birch, I heard a mushy thud. It was a dead sort of sound, like somebody dumped a shovel of wet sand into the boat.

“Shhhh!” Whispered Boze. “Keep your boots along the side of the boat, so you won’t kick the rib.”

“Wasn’t me,” I whispered back.

Turk turned his light to the bottom of the boat, first checking the gunwale ribs, then the keel line on the floor. Had we breached the bottom on a cypress knee? Suddenly Turk’s light froze on an object that looked like a radiator hose from a ’57 Chevy. In that soft yellow light, even I knew what was lying there. An old rule of the river flew through my brain: “Any fat object dropping into your boat at midnight is most assuredly a Cottonmouth Moccasin.” To my dismay, he was heading for sanctuary under my burlap sack.

“Moccasin!” I shouted. In more panic than reason, I tossed the burlap sack overboard. The snake immediately coiled in revenge for my having removed his intended refuge. My rubber boots were now only inches away, and certainly a foot shorter than I wish I had bought. Questions were cascading through my brain. Does light blind a snake like it does a frog? Is it true they can strike three times their length? When you slash and suck out the poison, what if you have a cavity in your tooth? I began to regret skipping my last dental appointment with Dr Pierpoint.

Suddenly the world’s tardy bell went off. Turk began beating at the snake with the frog gig, and Boze likewise with his boat paddle. They were flailing the boat bottom like fan blades. We were rocking and pitching wildly, and the flashlight rolled back and forth across the floor like a dance-hall strobe.

Then, with a lucky stab, Turk speared the snake. It coiled quickly around the gig, and I was able to grab the flashlight. Turk heaved the snake-wrapped gig toward the lake. It sailed away like a track-meet javelin. Turk grabbed the light from my hand and shined it around the inside of the boat.

“Look for another one,” he said. “Sometimes at night they twist around each other like black licorice.” I never liked licorice, but only now realized why.

Satisfied that nobody had been bitten and the snake was a loner, Boze pushed us back into the main part of the slough.

The journey back seemed to take hours, and I spent it in prayers of thanks. Like a pulsating star, the dim light of Pine Island Pier soon cut through the night. Its glow represented the warmest welcome I ever recall. I knew that just past the pier was Turk’s house, safe above the water on its ten-foot stilts.

Yep, there’s lots of religion in the swamp.

* * *

© Copyright 2005 by the author, Lad Moore

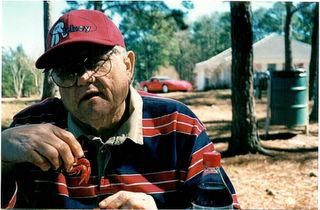

Illustration (C) Copyright by the artist, Jim Jurica. Used by license.

<< Home