birthright

My father’s work as a daredevil aviator and soldier of fortune called him to strange places around the world. His cable address, Tailwind, best summed up his spirit, and best portrayed how I remember him. He was forever rushing away, and my recollections of him are limited to the six short years we lived together.

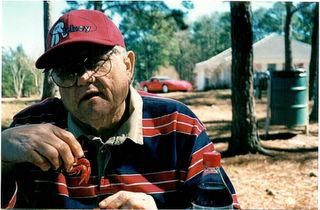

My favorite picture of my dad is the one in front of the Great Pyramids, wearing a fez and a crisp khaki uniform with an abundance of pockets on it. In the photo I can see a frozen swirl of dust behind him, and can almost hear the sound of the wind squeaking across the hot sand. I know that the smile on his face is fleeting—not lasting beyond the click of the camera shutter. I know that because in all my memories of him, I never recall him smiling or laughing. He was a terribly serious man, and his life was as hurried as his death at age 41.

In the time we lived and traveled together, I sailed the world on a freighter, visited dozens of exotic ports of call, and completed shipboard studies under the tutelage of a self-proclaimed Russian Prince. We lived in many lands, among them Burma, India, and Indonesia. Despite those countries’ differences, there was a strange sameness to them all. I found that the land and people were similarly humble, and Americans were viewed with an awe that was almost reverent. That awe is seemingly lost today, as Americans have somehow managed to become objects of scorn in lands that were once hospitable.

When I left to journey with my father to Asia, the Ladies Circle at our church gave me a Scofield Bible to take along. The church bulletin noted the event with the words, “May God’s hand go with this young man as he travels to far-off Bandung, where there is no Presbyterian Church.” The bulletin was right about the scarcity of organized religion, but we held our own services on Sunday evenings anyway. We met on the veranda of our home, a white stucco house with an orange tile roof in a dense mango grove. Many of the families of pilots who flew with my father came to the service, and there was no particular leader.

Like all other aspects of life in Indonesia, my religious exposure was crude and sometimes a little off the mark. Often we just held prayer and then watched westerns—films rented from a subscription service in the States. Other times we read scriptures together then adjourned for a sat¾ barbecue, a peanut-sauce kabob of ox meat and vegetables. The Baptists who came sometimes complained that the services were more celebratory than worshipful.

In my years of travel, I saw many of the great treasures of our world and its numerous natural and man-made wonders. But nothing I saw made my heart beat more furiously than the day we returned to New York Harbor. As the ship sailed past the Statue of Liberty, I recall standing on the deck and thanking God for my safe passage, then whispering the Pledge of Allegiance through the lump that almost blocked my airway. The cool spray of salt water crashing off the ship’s bow was like a fresh baptism to me. I had been away so long that familiar sights were like first-time discoveries. I thought…my how that statue must have looked to the hopeful immigrants who made this trip before me.

I was fourteen when my father died, and once again I returned to the quiet streets and neighborhoods of Marshall, Texas. I found the comforting things still there—the fireflies at night, the red glow in the sky from the rooftop sign on the Hotel Marshall, and the pew at First Presbyterian with our family name on it. It came to me that coming home is the best part of being away.

Despite the pressures and doubts we now feel so keenly, being an American is still the reward from our founders who proclaimed we were “One Nation Under God.”

There’s a saying that describes just how we Americans are blessed:

“We started life on third base, and we didn’t hit a triple.”

* * *

(C) Copyright 2006 by the author, Lad Moore

Image used by license. Image (C) by Sax, Dreamstime

<< Home