The Tale of Brassie McIe

“Austere perseverance, harsh and continuous—rarely fails of its purpose, for its

silent power grows irresistibly greater with time.” –Wolfgang von Goethe

It was 1920—a time of “Roaring” plenty for some, but not for all. On what is now the site of a renowned golf course near Austin, Texas, local legend tells of Silas McIe, a poverty-stricken farmer who toiled his land to wring out meager crops of cotton and beans. With a gimpy mule, Silas plowed his acres endlessly, removing the prolific rocks and stones to make way for the blades of the harrow. It was ruthless and disappointing work. The more he dug, the more stones he dislodged. To add insult to his never-ending task, the rocks seemed to re-emerge overnight, and the infrequent dashing rains always revealed more.

The people of the nearby town of Manor thought Silas strange, living alone as he did in the clapboard shack on the edge of the usually dry creek. The house was a weather-forgiving place, its roof nothing more than heavy mesquite thatch and its windows long abandoned of panes. The only proof of life was his candlelight at night, and the always-present wisps of smoke that danced from a crooked chimney pipe.

Unshakable determination was a hallmark of the McIe mystique, and considerable money changed hands when farmers around Manor bet on the success or failure of his crops. Some years he fooled them all, bringing in 20 bales of cotton or more. Other years they saw no crop at all. But there was one thing that they could count on. Every Saturday would be another “Brassie McIe Day”—the nickname given to Silas by his observers.

After good daylight on Saturdays, a number of people from Manor always traveled to the McIe farm, parking their wagons as close to the gate as possible. Silas’crude-lettered sign, “No Trespassing-Even with Permission” blocked any intrusion beyond the gate. Some thought the words were humorous--others believed them ominous, even frightening. For years, the ladies of Manor said old Silas walked the grounds with a shotgun. But “Brassie Day” proved that the “weapon” was not a shotgun at all.

Brassie Day always stirred a festive picnic atmosphere. Town folk sat on wagon sideboards and wooden benches they brought to the site. Families brought covered lunches and the men stuffed extra pouches of their favorite tobacco into their overalls pockets. Folks settled in for a long day, and waited patiently for Brassie to emerge and his “oddity pastime” to begin.

As dependable as daybreak, Brassie always showed. He strode across the field, dressed in knickers and a crumpled cap, with a single golf-iron in his hand. With each swing of the club, a small stone would whiz away, often sounding like the whir of a locust as it sailed through the air. He never missed—one swing, one stone.

It would have been foolish to bet against his aim. The rocks always landed in the creek bed, precisely at the north edge, and all within a ten-foot circle. In time, given his accuracy, the pile of stones formed a mound as high as a man’s waist. It remains there today—a monument to the passionate perseverance of Brassie McIe.

The tale goes on to say that on Saturday August 24, 1929, spectators did not see Brassie at his usual time. After a two-hour wait, two men from town ventured beyond his gate and walked to the little house. After no answer at the door, they went inside. Brassie was there, sitting at a rough-hewn table, with his knickers and hat. His eyes were open but he did not see.

On the wall over the fireplace was a hand-rubbed mesquite plank with forks of deer antlers attached to each end. The antlers served as a kind of cradle for Brassie’s golf iron. The club was crudely made, fashioned from a heavy steel rod. Its grip was wrapped with deer hide worn slick by oily sweat. The clubface was hammered with dimples and grooved from countless encounters with stone.

Affixed to the plank was said to be an inscription, engraved on a shiny copper sheath. It read:

“Oh golf, thou hath stolen my soul.”

* * *

© Copyright 2005 by the author, Lad Moore

Fallen Leaves

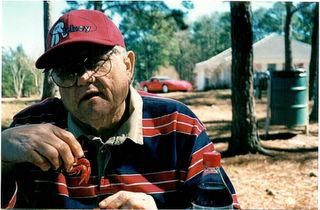

Your Dad Misses You... Lad Moore III--1965--1999

Your Dad Misses You... Lad Moore III--1965--1999

Fall and the holidays were his favorite time of year. When fortunes brought him home for the Thanksgivings of his last years, it was like reliving the times of his boyhood. The scenes were scripted--Macy's Parade as background noise, Mom in her apron fussing in the kitchen, and a really bad Detroit Lions game on TV. The air would be fresh and crisp, and much of the fall color would still be visible in the leaves that danced around the yard. At halftime we were never too old to go outside and throw the football a few times, but nothing like the days of his youth when he and his brother allowed me to be "all-time quarterback". They cut me this honor because as the years went by, I could not keep up with their deep routes and never was much good at catching the ball. My youngest son would fight to the end against his larger brother, often riding him piggyback into the endzone--that invisible line next to the azalia bed. Sometimes the front of his jeans were moist--a little dribble rather than breaking huddle to go inside to the bathroom. Game over, Lad III would irritate his mother by "testing" the turkey before it was time. He was after the crispy part of the golden skin of an always-perfect bird. This was mom's little irritant--which carried a penalty of a soft pat on the offending hand. At precise timing to the "Amen" of the blessing, Lad claimed one of the drumsticks. He needn't have rushed, because nobody ever fought him over it. After all, who wants to contend with those little sword-like splines when staring at a Butterball breast still bubbling its juices?

After the meal came the second game of a double-header--just in time to ease the stress of an overfilled paunch. Most often Texas played A&M. Mostly A&M lost--unless you count the halftime band performance.

Today I approach very different Thanksgivings. Lad III is gone, as is the Texas/A&M game on TV. My youngest usually can't make it here--there are job and mile issues. Maybe the Lions still play that day--I don't know. But my yard will be empty at halftime. That is, except for the leaves--still full of color, and still scurrying in circles in the crisp fall air.

The Nine Lives of the Inanimate

I should have kept my Tupperware glasses, even though they were dishwasher-warped and the kids had chewed on their rims—turning the edges into a sort of makeshift dental floss.

* * *

The Channel 12 weatherman said today was the first day of summer. In a sort of impromptu celebratory toast with my cran-apple juice, I raised my glass in tribute. It struck the edge of the kitchen cabinet and slipped from my grasp. The glass soared like a rocket toward my brick floor, despite my flailing for it on its way down. It more than just broke—it imploded—like how they collapse old hotels with dynamite. It was playful glass—the kind that scatters on impact like summer rain on the freshly waxed hood of a car. Pieces scampered to the safety of the braided rug, and others raced for the darkness under the dishwasher vent-thing. More agile fragments mounted dust-bunnies and rode them out of the room.

I swept the kitchen, using the same grid-pattern used to ensure the integrity of archeological digs. Then I vacuumed every square inch, and beat the fiber out of my braided rug with my husband’s tennis racket. Lastly, I mopped—including Q-tipping the baseboards. I made sure the infected sponge head was hermetically bagged and tossed, which was a heroic act of sacrifice in itself. I had to fight a nagging temptation to just rinse off the sponge and give it to my husband for scrubbing out the pickup bed. He would never know, and hey—it’s just a truck for God’s sake. In the end I conceded to honesty. It’s only $2.00, and sometimes the Dollar Store has them 2 for $3.29 with a coupon.

On Sunday I located a surviving sliver of juice glass with the naked heel of my foot. I had fretted one might show itself, but cast aside my fears. After all, the statute of limitations for orphaned glass had comfortably passed—signaling it was safe to go barefoot again. And Muffy had done reconnaissance for me when he went to his food bowl at least six times without even the hint of a limp.

I could feel the glass when I caressed the spot with a loving finger, but I couldn’t see or grasp it. Its pesky little tip retreated like a taunting turtle. Doctors lie when they say that glass will work itself out. It only works itself near. Surgery was clearly indicated.

I poked and probed the spot with a needle until my self-inflicted wounds dwarfed the original injury. Multiple epithets ended the operation without confirming if success had been achieved.

It is now Labor Day. The spot of my summer surgery has hardened into a kernel the size and color of a pencil eraser. It is resistant to even the most aggressive of emery boards. It remains just rough enough to provide the leadership for the first tear in my panty hose.

And it is always first in line to announce that my newest shoes should have been a half-size larger.

# # #