Something to Be Said

I love small towns. They make me feel so far removed from the awful events of Iraq and world terror. Small towns give me recess from anguish—I suppose because the pace is slow and the volume low.

Yesterday I prepared three manuscripts to mail internationally. Two were going to Canada, and one to the United Kingdom. All three required a return envelope with International Reply Coupons. I went to the local post office to obtain the coupons and finish the mailings.

US Post Office, Woodlawn TX, Population 283

The local postmistress greeted me with a wide arching wave—a colloquial howdy. She was eating a Snickers candy bar while Judge Judy screamed at a defendant on the television.

“International what? I don’t recall ever having such,” she said. “What in creation would you do with one?”

I explained their purpose.

“Guess we’ve never had a call for one,” she said. You better try over to the Jefferson office. But mind you they close at four.” My watch read 3:20 PM.

US Post Office, Jefferson TX, Population 1,864

I arrived at 3:49--breathing hard from trotting through the parking lot with my parcels.

The clerk was a stout woman of about fifty, and she began to drum her fingers on the counter as I explained what I needed. Her level of attentiveness seemed compromised as she examined me over the rims of her glasses.

“I’ve heard of those,” she said. She turned to another clerk in the adjacent cubicle.

“Carl! Don’t we have those foreign return things?” I could see that Carl’s wheels were turning.

“I think they’re those yellow slips in the safe.” Carl had a curious task of his own. He was artistically arranging a row of stamps on a tubular package big enough to contain a set of water skis.

“Get one of them out and show it to him.” Although Carl was mostly obscured by the large tube, one arm ventured out and pointed toward the safe.

The woman disappeared through a plastic hanging curtain—the kind that lift trucks part and pass through. She returned a few minutes later, rubbing the coupon on her sleeve so as to slick it up.

“Is this it? This old thing? Look at all those funny words on it. Is that French, or what?” She turned away, shouting over the partition that was plastered with faded wanted posters.

“Carl! This thing is marked $1.05. Is that an old price? Is that what we still charge?

She looked down at me reassuringly, with the kindness of a doting aunt.

“I think foreign postage may have gone up a smidgen,” she warned, trying to prepare me for the dime or quarter hike that Carl was likely contemplating.

“Sell it for the $1.05 if he wants it, I don’t know the price.”

With the water ski box now on the outbound conveyor, Carl took over the woman’s counter position.

“Okay, next customer," he said, straining on his tiptoes to see over my head. He motioned me to the side, waving his hand briskly as if fanning a campfire.“Oh! Sorry,” I said, feeling a bit humbled. I moved to the far end of the counter amidst furrowed frowns and curious stares from the patrons.

“How many of these do you want?” The woman asked.“I’ll need three of them,” I said. Once again she disappeared behind the lift truck curtain. “No, wait,” I shouted. “Better give me six, so next time I won’t have to drive over here. They don’t have them in Woodlawn.”

She emerged from the safe room, once again buffing the coupons on her sleeve.

“I guess they’ve been locked up in there all this time, but I could only find two. I suppose you can have them both, and then we’ll be done with them.” I took her remark to mean there would be no restocking of the safe.

I carefully thought about which two of the packages should get the coupons. I decided that the third recipient would have to be happy with cash, and I placed a dollar and a nickel inside the one destined for the UK. Maybe the person opening the package would note my Woodlawn return address and somehow forgive my decision.

I chose the UK destination because I know that Tony Blair and those folks are among our only remaining friends.

* * *

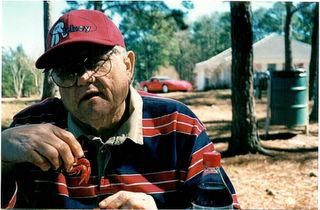

(C) Copyright 2006 by the author. Illustration by license from the photographer, Bradley I. Marlow