The Papoose Men

“The misery of a child is interesting to a mother, the misery of a young man is interesting to a young woman, the misery of an old man is interesting to nobody.”

—Victor Hugo

* * *

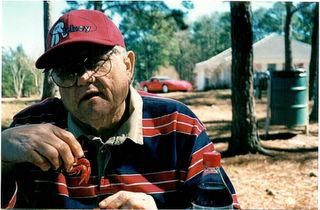

The no-frills Hotel Washington was already past old when I first entered its lobby. It sat near the end of Marshall Texas’ Washington Street, its scaling decorative edifices speckled with the dispatches from hordes of pigeons. The birds were at home there because of their sponsors. Little old men, with backs bent from toil and trouble, called the hotel home. They were the distributors of stale bread and popcorn that kept the pigeons there. It was sustenance for the birds, and activity for the men who longed for a way to pass the days. The Washington was no longer the hotel originally built to catch the overflow patrons when its rival Ginocchio Hotel sold out, or to offer a choice for the less-affluent rail passengers. Still but a short walk from the Texas and Pacific Depot, it now had now become a budget residence-inn.

My newspaper job took me to the Washington as my first stop. I sold papers along a walking route that included most of the downtown area. It was not a throwing route, but was sell-on-demand. Some stores and businesses had monthly accounts, but even these had to be hand delivered inside, not tossed on doorsteps.

Many of the old men who hailed from the once-thriving Texas & Pacific shops and the Car Wheel Foundry inhabited the hotel. Some were disabled but could not qualify for long stays at the T&P Railroad Hospital, so instead they took up residence at the Washington. When I mingled among them there was an air of sadness—often I heard recitations and regrets over what once had been proud and gainful work with the railroad. They would describe those times as the best years of their life, paying a sort of paternal reverence to their employer. Each man could raise a tale about his time there, some happy, some dark.

One gentleman wearing an eye patch told me he was “deadly sure that a body or more” had been dumped into the molten iron vats in the wee hours of the early morning when supervision was sparse. “Settling union business,” he said. I expected him to end his tale with the classic pirate “aargh.”

Another fellow they called Old Man Abraham once told me about some women who worked at the shops called the “Loosies of the mid-hour.” He said it was common for men to pair up with the Loosies after midnight and seek out romantic interludes on the heaps of corn that were stored in the adjacent grain mill and elevator.

“I could slip down there before midnight and stash myself in the mill behind the stacks of old pallets and keep real quiet. I could hide and watch the spooning. Ten years ago you could have done that too,” he said. Then he showed a gaping smile revealing no more than four teeth, all the color and shape of acorn hulls. His tales caused my face to turn red so I began to avoid eye contact with him altogether. I admit that some curiosity did linger so I asked my uncle SB about spooning. He said I should tend to my geography book and leave “higher education” to grown ups. I doubted that anything like spooning took place at the Washington. I don’t even think I ever saw a female there. It seemed to be just a lodge for these old men who came to spend a while but stayed.

Behind the clerk’s counter there were room-key slots serving double-duty as repositories for the infrequent mail that arrived for tenants—their only link to elsewhere. Like the daily assemblage of pigeons, each mail delivery found the old men clustered around the counter with a watchful eye on their slots. The mail bag was quickly sorted, and most of them moved away in silence, empty-handed, and with brows a bit more furrowed. Mail call was for many the only activity for the day. It was followed by a slow houseshoe-shuffle to creaky wooden chairs—their bottoms worn slick by decades of quiet patronage. Even in the heat of summer, some of the men spread wool blankets or folded shawls across their chilled legs—legs white from years without sunlight and braided with trails of blue and purple veins.

In the lobby there were two tables for dominos, and the clacking of ivory was the only sound besides the beat of the Western Union wall clock. But even the dominos went silent if someone entered the hotel. All eyes would turn and plead for even the briefest of contact—perhaps nothing more than a “good morning” greeting or the arc of a wave. But visitors rarely did so. They came to the hotel out of chore. They brought the mail or delivered chicken and ham-salad sandwiches ordered daily from the drug store lunch counter. Meter-readers came once a month but never stepped inside. Other men with gurneys sometimes came on sadder missions; to retrieve a body that had failed morning muster. It seemed odd to me that there was no rear door for that purpose.

.

I didn’t sell many papers at the hotel because the old men had worked out a system where a few bought papers and passed them around to others like a family-style dinner. One would start with the sports pages then them in trade for the “A” section. The next day they reversed the order. It was also “dry” in there, meaning I never got a tip.

The hotel was my first newspaper stop so I arrived early, about the time the men began to stir. My other customers’ stores rarely opened until eight or nine, so I often wasted my first hour of the day soaking up the character and curiosity of the place.

Each morning there assembled two or three husky young black men that the tenants called “Porter Jim” or “Porter Sam” or Porter-whatever. Several of the residents could not climb the flights of stairs, so they mounted the backs of the porters who carried them downstairs piggy-back style. Instead of calling them porters, I dubbed them “Papoose Men” because they reminded me how Indians carried their young. They worked for tips, disappearing after the morning rides and reappearing in the late afternoon to repeat the process. I don’t know where they went during the day, or what they did for other work.

I thought it curious that these porters were so reliable in their service, because the old men had little to share, and the tips must have been meager. I asked one of the Papoose Men why he came day after day to help the old men. He paused for what seemed like a minute then answered in one word.

“Dignity.”

Long after my walking route ended and a few steel newspaper racks took my place, I would pass by and linger at the door of the old Washington. I saw fewer and fewer men now, and less and less mail. Then after a lengthy absence, I returned one day to find the hotel boarded up and silent. Even the pigeons had retreated to the rail yards where the mill elevator cars provided a more reliable supply of spilled grains.

That day I pressed my face against a crack in the planks that covered the windows, hoping for one last look at a history I had lived. I could see nothing inside except for a single shard of sunlight that lasered its way from somewhere above me onto the dust-covered lobby floor. It was like a spotlight focused upon an empty stage; a stage that once provided me memorable theatre—the ordinary, and yes, the extraordinary.

* * *

Story © Copyright 2009 by the author, Lad Moore. All rights reserved.

Image © Copyright by the photographer, Alexander Ritter, compensated for license.

—Victor Hugo

* * *

The no-frills Hotel Washington was already past old when I first entered its lobby. It sat near the end of Marshall Texas’ Washington Street, its scaling decorative edifices speckled with the dispatches from hordes of pigeons. The birds were at home there because of their sponsors. Little old men, with backs bent from toil and trouble, called the hotel home. They were the distributors of stale bread and popcorn that kept the pigeons there. It was sustenance for the birds, and activity for the men who longed for a way to pass the days. The Washington was no longer the hotel originally built to catch the overflow patrons when its rival Ginocchio Hotel sold out, or to offer a choice for the less-affluent rail passengers. Still but a short walk from the Texas and Pacific Depot, it now had now become a budget residence-inn.

My newspaper job took me to the Washington as my first stop. I sold papers along a walking route that included most of the downtown area. It was not a throwing route, but was sell-on-demand. Some stores and businesses had monthly accounts, but even these had to be hand delivered inside, not tossed on doorsteps.

Many of the old men who hailed from the once-thriving Texas & Pacific shops and the Car Wheel Foundry inhabited the hotel. Some were disabled but could not qualify for long stays at the T&P Railroad Hospital, so instead they took up residence at the Washington. When I mingled among them there was an air of sadness—often I heard recitations and regrets over what once had been proud and gainful work with the railroad. They would describe those times as the best years of their life, paying a sort of paternal reverence to their employer. Each man could raise a tale about his time there, some happy, some dark.

One gentleman wearing an eye patch told me he was “deadly sure that a body or more” had been dumped into the molten iron vats in the wee hours of the early morning when supervision was sparse. “Settling union business,” he said. I expected him to end his tale with the classic pirate “aargh.”

Another fellow they called Old Man Abraham once told me about some women who worked at the shops called the “Loosies of the mid-hour.” He said it was common for men to pair up with the Loosies after midnight and seek out romantic interludes on the heaps of corn that were stored in the adjacent grain mill and elevator.

“I could slip down there before midnight and stash myself in the mill behind the stacks of old pallets and keep real quiet. I could hide and watch the spooning. Ten years ago you could have done that too,” he said. Then he showed a gaping smile revealing no more than four teeth, all the color and shape of acorn hulls. His tales caused my face to turn red so I began to avoid eye contact with him altogether. I admit that some curiosity did linger so I asked my uncle SB about spooning. He said I should tend to my geography book and leave “higher education” to grown ups. I doubted that anything like spooning took place at the Washington. I don’t even think I ever saw a female there. It seemed to be just a lodge for these old men who came to spend a while but stayed.

Behind the clerk’s counter there were room-key slots serving double-duty as repositories for the infrequent mail that arrived for tenants—their only link to elsewhere. Like the daily assemblage of pigeons, each mail delivery found the old men clustered around the counter with a watchful eye on their slots. The mail bag was quickly sorted, and most of them moved away in silence, empty-handed, and with brows a bit more furrowed. Mail call was for many the only activity for the day. It was followed by a slow houseshoe-shuffle to creaky wooden chairs—their bottoms worn slick by decades of quiet patronage. Even in the heat of summer, some of the men spread wool blankets or folded shawls across their chilled legs—legs white from years without sunlight and braided with trails of blue and purple veins.

In the lobby there were two tables for dominos, and the clacking of ivory was the only sound besides the beat of the Western Union wall clock. But even the dominos went silent if someone entered the hotel. All eyes would turn and plead for even the briefest of contact—perhaps nothing more than a “good morning” greeting or the arc of a wave. But visitors rarely did so. They came to the hotel out of chore. They brought the mail or delivered chicken and ham-salad sandwiches ordered daily from the drug store lunch counter. Meter-readers came once a month but never stepped inside. Other men with gurneys sometimes came on sadder missions; to retrieve a body that had failed morning muster. It seemed odd to me that there was no rear door for that purpose.

.

I didn’t sell many papers at the hotel because the old men had worked out a system where a few bought papers and passed them around to others like a family-style dinner. One would start with the sports pages then them in trade for the “A” section. The next day they reversed the order. It was also “dry” in there, meaning I never got a tip.

The hotel was my first newspaper stop so I arrived early, about the time the men began to stir. My other customers’ stores rarely opened until eight or nine, so I often wasted my first hour of the day soaking up the character and curiosity of the place.

Each morning there assembled two or three husky young black men that the tenants called “Porter Jim” or “Porter Sam” or Porter-whatever. Several of the residents could not climb the flights of stairs, so they mounted the backs of the porters who carried them downstairs piggy-back style. Instead of calling them porters, I dubbed them “Papoose Men” because they reminded me how Indians carried their young. They worked for tips, disappearing after the morning rides and reappearing in the late afternoon to repeat the process. I don’t know where they went during the day, or what they did for other work.

I thought it curious that these porters were so reliable in their service, because the old men had little to share, and the tips must have been meager. I asked one of the Papoose Men why he came day after day to help the old men. He paused for what seemed like a minute then answered in one word.

“Dignity.”

Long after my walking route ended and a few steel newspaper racks took my place, I would pass by and linger at the door of the old Washington. I saw fewer and fewer men now, and less and less mail. Then after a lengthy absence, I returned one day to find the hotel boarded up and silent. Even the pigeons had retreated to the rail yards where the mill elevator cars provided a more reliable supply of spilled grains.

That day I pressed my face against a crack in the planks that covered the windows, hoping for one last look at a history I had lived. I could see nothing inside except for a single shard of sunlight that lasered its way from somewhere above me onto the dust-covered lobby floor. It was like a spotlight focused upon an empty stage; a stage that once provided me memorable theatre—the ordinary, and yes, the extraordinary.

* * *

Story © Copyright 2009 by the author, Lad Moore. All rights reserved.

Image © Copyright by the photographer, Alexander Ritter, compensated for license.

Labels: short stories